“If man in the state of nature be so free, as has been said; if he be absolute lord of his own person and possessions, equal to the greatest, and subject to no body, why will he part with his freedom, this empire, and subject himself to the dominion and control of any other power?”

John Locke, 1690, Second Treatise of Government, Ch. IX, sec. 123

The State of Nature

Imagine a world with no laws, governments, or set structures of morality dictating to us what is right and wrong.

We are not constrained by codes of conduct demanded from the civil society we know today. We are in essence, lone, independent beings, purely working from the thoughts and behaviours we naturally would have.This pre-social condition is what philosophers called the State of Nature. The State of Nature is what it would look like before we developed any social structures. In other words, the state of our being if we were uncontrolled and left to our own natural intent; and the type of environment that would create. Philosophers had different thoughts of what kind of world that would be.

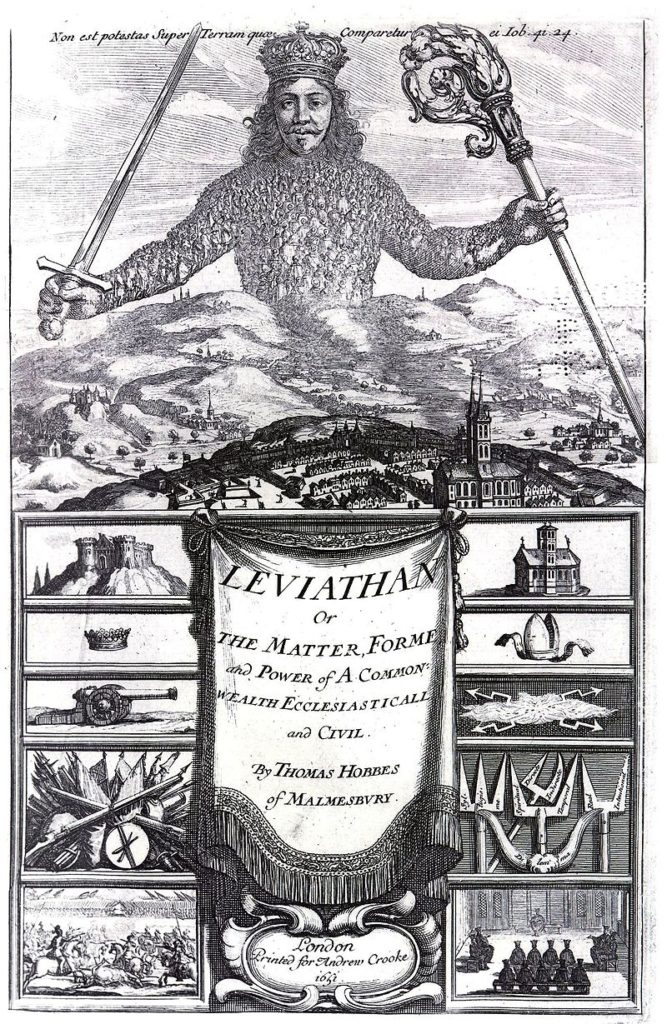

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) had, what many see as, quite a grim perspective on the real essence of human nature.

Hobbes believed that ultimately, people were only concerned with themselves and purely motivated by self-interest. Hobbes believed that the State of Nature would be a state of war; a constant battle for survival. Without law or threat of punishment, he believed that human nature would wreak havoc. He famously said that life in the State of Nature would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. Left to our own inherent devices, we would have a ferociously violent environment, due to unrestrained instinct, necessity to survive and no fear of punishment. We would be in a constant state of fear, knowing that everyone was concerned with self interest alone.

“To this war of every man against every man, this also is consequent; that nothing can be unjust. The notions of right and wrong, justice and injustice, have there no place. Where there is no common power, there is no law; where no law, no injustice.” Thomas Hobbes, 1651, Leviathan, The First Part, Chapter 13

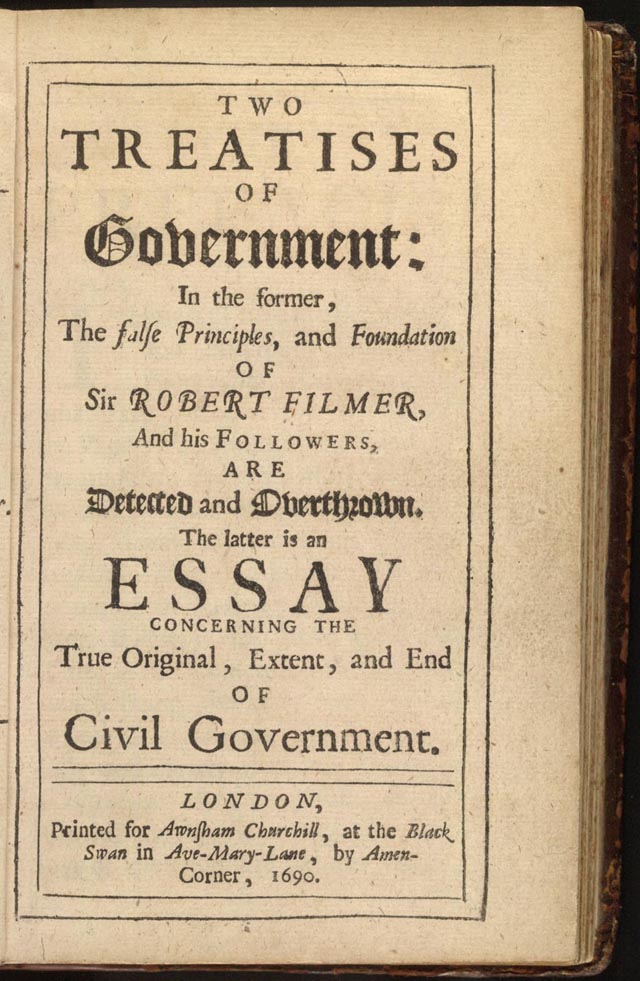

John Locke (1632-1704) disagreed with Hobbes. He thought that even though The State of Nature is a pre-social state, it still has morality.

Locke believed that within The State of Nature, the Law of Nature would still exist, as these were laws given to us by God. These Laws of Nature are inherent liberties, which conduct our moral behaviour, accessed through our ability to reason. The State of Nature would be a place where people lived independently and equally. Locke believed the Law of Nature would direct people in the State of Nature- “…that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions…”.

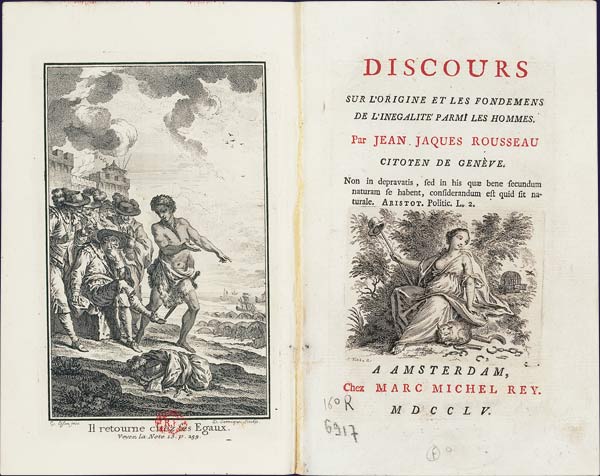

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) also had a very different idea than Hobbes of the State of Nature. Rousseau believed it to be a peaceful time where people largely lived solitary lives.

He thought in some ways contemporary humans at a disadvantage; in the State of Nature people were uncorrupted by society and were essentially free to do as they please. It would have been a largely peaceful time Rousseau thought, as he believed that human nature was essentially good. But everything changed when people began living in close quarters. Like Locke, Rousseau sites private property as the death of the simple, peaceful times that were the State of Nature.

“The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said “This is mine,” and found people naïve enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.” Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1754, Second Discourse, The Second Part

The Social Contract

Although Hobbes believed human nature was driven by self-interest, he also believed people to be reasonable.

It was because of this that he believed people voluntarily engaged in the Social Contract. People agree to give up some of the freedoms they would have in the State of Nature in return for safety. They agreed to laws which would resist them the right to do harm to others, in return of the same. By part-taking in social conformities, they escaped the dangerous State of Nature giving them further hope of survival. Hobbes believed it is due to this contract that people act morally, as opposed to an inherent code of morality. Hobbes went on to state that there needed to be a sovereign figure which would insist on the social contract being implemented; a sovereign that must never be challenged. The sovereign demands co-operation amongst men; the failing of which will result in punishment. People adhere to this idea of Justice because it protects them from the State of Nature.

“For the laws of nature, as justice, equity, modesty, mercy, and, in sum, doing to others as we would be done to, of themselves, without the terror of some power to cause them to be observed, are contrary to our natural passions, that carry us to partiality, pride, revenge, and the like. And covenants, without the sword, are but words and of no strength to secure a man at all.” Thomas Hobbes, 1651, Leviathan, The Second Part, Chapter 17

Locke believed that people engage with the Social Contract because even the Law of Nature needs guidance and regulation.

“It is unreasonable for men to be judges in their own cases, that self-love will make men partial to themselves and their friends: and on the other side, that ill nature, passion and revenge will carry them too far in punishing others; and hence nothing but confusion and disorder will follow…”. It is in essence a more explicit and governed Law of Nature we were searching for when we embarked on civil living according to Locke. He did not agree with Hobbes that the sovereign in charge of implementing these rules should always go unchallenged. He believed that they are there in order to serve and protect the people and their rights. Locke concluded that if the Sovereign is no longer serving that purpose or is acting tyrannical, the people have the right to over throw them.

“This is to think that men are so foolish that they take care to avoid what mischiefs may be done them by polecats or foxes, but are content, nay, think it safety, to be devoured by lions.” John Locke, 1690, Second Treatise of Civil Government, Chapter 7, Sec 93

Hobbes believed there is no possible situation in a civil society that could be worse than the State of Nature, so in turn, the sovereign who protects us from it, should be all powerful. Locke however, could see situations in society where people may have reason to revert back to it, given his more optimistic view of how life would be in the State of Nature.

In Plato’s ‘Crito’ (360 BC approx.), a dialogue occurs between Socrates and Crito which, with quite a lot of honour, outlines the idea later termed as the Social Contract.

Socrates is awaiting his death, a penalty which was decided by his Government. When Crito implores Socrates to escape and flee his execution, Socrates says to Crito “In leaving the prison against the will of the Athenians, do I wrong any? or rather do I wrong those whom I ought least to wrong? Do I not desert the principles which were acknowledged by us to be just?”. Socrates says that once one becomes an adult, they can decide for themselves whether to stay and abide by society, or to leave. Speaking as the Laws of Athens he says “Any of you who does not like us and the city, and who wants to go to a colony or to any other city, may go where he likes, and take his goods with him. But he who has experience of the manner in which we order justice and administer the State, and still remains, has entered into an implied contract that he will do as we command him.” Socrates speaks of a sense of duty and appreciation to a society that gave him existence and education. He could not then, betray that same society by running from its laws, which he implicitly agreed to by remaining a citizen. Socrates believed he should keep his word as a citizen and, having reaped the benefits of being in the society, should accept its account of justice also.