“I know the hatred and envy of your hearts. Ye are not great enough not to know of hatred and envy. Then be great enough not to be ashamed of them!” (Friedrich Nietzsche, 1891, Thus Spake Zarathustra, War and Warriors)

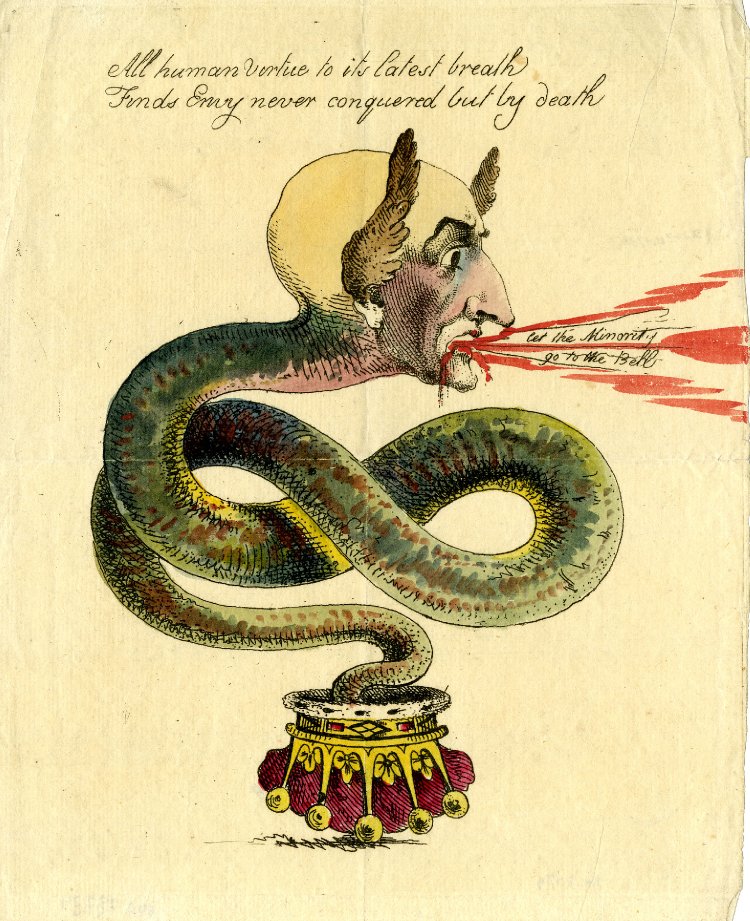

Envy

The Grimm’s German dictionary compiled in the 19th century provided the following definition of envy: “envy expresses that vindictive and inwardly tormenting frame of mind, the displeasure with which one perceives the prosperity and the advantages of others, begrudges them these things and in addition wishes one were able to destroy or to possess them oneself.”

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) believed that envy was natural to man and therefore part of us all. He believed that envy came about in ‘the inevitable comparison between our own situation and that of others.’ When we compare ourselves to others, we highlight our differences and in doing so, highlight our own inferiorities. We start believing that we are unhappy because of these things we lack in comparison, and envy creeps in.

Malicious Envy

“To feel envy is human, to savour schadenfreude* is devilish.” (Arthur Schopenhauer, 1850, On the Suffering of the World)

(*Pleasure derived from another’s misfortune.)

When we feel inferior in some way upon comparison, it can lead us to believe that the one we deem superior is our enemy.

We can believe that our unhappiness is directly associated with that person’s perceived or real, superiority. The greater the talent of that person, the more we hate them, as it accentuates even more, our own inferiority. The fate of our happiness is now tied to that person’s position. The gap between us and them, filled with our own shortcomings, is painful and makes us uncomfortable. In order to close that gap, we focus our time and efforts on destroying or diminishing that which we are envious of. In this act, the main priority is not to acquire what we are envious of, but to strip them from the superior. By doing so we needn’t spend any effort elevating ourselves to the heights of those we envy, we simply tear them down.

“Mortals are easily tempted to pinch the life out of their neighbor’s buzzing glory, and think that such killing is no murder.” (George Eliot, 1871, Middlemarch, Chapter XXI)

Malicious envy can work in many forms, not just in the direct destruction of the person envied.

People, individually and collectively, may try to lower standards or expectations in order to minimize the disparity between those standards and their own conduct or achievements. We can blame others, claiming a direct causation between their misfortunes and the other people’s good fortune- ‘We’re poor because you’re rich’. We can attack ideals held, perhaps by stating they are bias, or

by belittling their value. There are various ways malicious envy closes the gap by means of lowering the bar.

“Feeling inferior, he will have a grudge against those who seem superior. He will find admiration difficult and envy easy.” (Bertrand Russell, 1930, The Conquest of Happiness, Chapter 7)

Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) and Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) both observed the concept of ‘ressentiment’. This concept describes how we reassign the responsibility of our own inadequacies onto others. In doing so, the pain we feel because of our own faults is the doing of another. We are relieved of the need to look inside and face our own deficiencies; we can, instead, blame an external evil for our short comings.

“Nothing on earth consumes a man more quickly than the passion of resentment.” (Friedrich Nietzche, 1888, Ecce Homo, Why I am so Wise, Part 6)

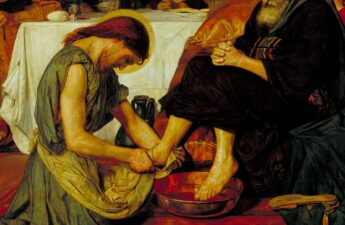

Benign Envy

“They envy the distinction I have won; let them, therefore, envy my toils, my honesty, and the methods by which I gained it.” (Sallust, 86-34 BC)

As previously stated, Schopenhauer suggested that envy is part of human nature and so, part of us all.

We still compare ourselves to others, and, inevitably come up short. We are still then faced with the gap between us and another, between where we are and where we want to be. Envy still exists, but how we use it may differ. In his second book of Rhetoric, Aristotle (384- 322 BC) made a distinction between ‘phthonos’ (envy) and ‘zelos’ (emulation). Although both forms of envy, he suggested that they differ. Zelos meant a man desires the things his neighbour has for himself, while phthonos meant a man desires to deprive his neighbour of those things. He believed zelos could be a positive drive for people to improve themselves in order to better emulate a superior.

“You can get away from envy by enjoying the pleasures that come your way, by doing the work that you have to do, and by avoiding comparisons with those whom you imagine, perhaps quite falsely, to be more fortunate than yourself.” (Bertrand Russell, 1930, The Conquest of Happiness, Chapter 6)

This offers a change in direction when faced with the disparities between us and them.

Instead of aiming to bring down those we perceive as superior in order to close the gap, we instead elevate ourselves up to their level. It is this crucial difference Aristotle spoke of that can change how envy affects us. Malicious envy will never allow us to achieve greater heights, since the real aim is to tear down, or blame another, not to enhance our own prospects. Emulation can force us to look at ourselves and what changes we could make in order to attain what another has. One is destruction, the other creation. Those we envy are no longer the enemy, but an example, a possibility even. A measurement of success from which we can plan an upward trajectory.

“Nothing sharpens sight like envy.” (Thomas Fuller,1608-1661)

Thank you! Shared!