“Temperance is reason’s girdle and passion’s bridle, the strength of the soul, and the foundation of virtue.”

Jeremy Taylor, reported in Josiah Hotchkiss Gilbert, Dictionary of Burning Words of Brilliant Writers (1895)

What do we know about temperance?

From 1920 to 1933, it was illegal to produce and sell alcohol in the United States. It was largely the work of The Temperance Movement which led to the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment- criminalising the production, distribution or selling of alcohol. The Temperance Movement were a group of people who advocated abstinence from alcohol, believing it to be sinful and damaging to work life, home life, and the spirit.

We now know that the Prohibition was ultimately a failure, seeing a surge in bootlegging and organised crime; home brewing with some deadly results; overcrowded jails and a general sense of disobedience from the public. Due to this recent history, the term ‘temperance’ has long been associated with a strict, ascetic lifestyle; not something we would couple with pleasure or enjoyment. If we reach back a little further however, the virtue of temperance was never meant to be an extreme.

Why are we talking about temperance?

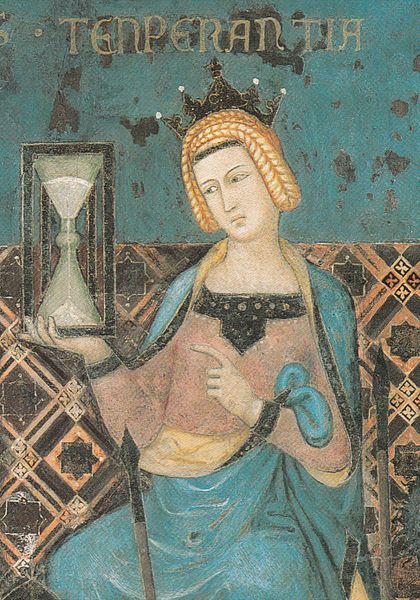

In Classical Civilisation and in traditional Christian Theology, they recognised four cardinal virtues- prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. The word ‘cardinal’ derives from the Latin word ‘cardo’, meaning hinge. The four cardinal virtues are called so because they are seen as necessary to the existence of all other virtues; for example- we cannot be loyal without fortitude; we cannot be honourable without justice, etc. They are the foundation to all other virtues.

In Buddhism, temperance is an essential part of the Eightfold Path. In Hinduism, the concept of ‘Dama’, which is said to be equivalent to temperance, is written about in sacred scriptures dating back as far as 700 BC. For thousands of years, across various cultures, temperance has been seen as a fundamental virtue in leading a moral and worthwhile life. Many great philosophers emphasised the importance of temperance in their writing; Plato, Cicero, Thomas Aquinas, Aristotle, Seneca, etc; alluding further to its major significance.

The Mean

“For both excessive and insufficient exercise destroy one’s strength, and both eating and drinking too much or too little destroy health, whereas the right quantity produces, increases or preserves it. So it is the same with temperance, courage and the other virtues… This much then, is clear: in all our conduct it is the mean that is to be commended.”

Aristotle, 350 BC, The Nicomachean Ethics

As we have said, temperance is often associated with severe austerity; a spartan existence, where denying oneself of any and all pleasures is central. This kind of extremity however, is in conflict with the essence of temperance. Temperance is not about prohibiting pleasure, it is concerned with the improper use of it; when the indulgence or pursuit of pleasure verges towards the destructive.

Temperance means moderation, the balance, the mean. It is neither excessive or deficient, it is just enough to create an environment in which to thrive. Imagine the extremes on either end of the scale are on fire. We must fight to stay in the middle for if we verge off towards either extreme, we get burned. The most obvious example is food. Too little, we starve, too much we are immobilised and suffer gravely. But with a balanced diet, food enables us to function just as we should.

“So called pleasures, when they go beyond a certain limit, are but punishments.”

Seneca, approx 65 AD, Letters from a Stoic

This concept of moderation was often spoken of in reference to food, alcohol, lust- human desires that people typically over indulged in. The same concept of moderation however, was discussed in reference to virtue itself. Our behaviour, our actions and our virtues are all best when in moderation-“Now moderation is needed, not only in desires and pleasures, but also in external acts and whatever pertains to the exterior. Therefore temperance is not only about desires and pleasures.” (Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1485 (published), IIa IIae 141.3)

Let’s take courage, for example. When courage is non-existent we find timidity or cowardice. When we go to the extreme on the other end of the scale, we find recklessness and the foolhardy. But right in the middle, we find courage in its noble and celebrated form. By running at either end of the scale we risk getting burned, but right in the middle we, and our virtues, flourish and thrive.

Restraint

“For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places.”

Ephesians 6:12, KJV

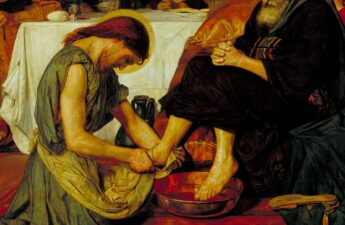

Thomas Aquinas in Summa Theologica discussed in detail how some of our natural passions and desires, when pursued without restraint, do not serve us well now or in the future. Part of temperance is using reason to recognise that although indulgence may give us short term gratification, it is not the best choice for us in the long term. Self-restraint gives us the power to take our eyes away from this instant and look beyond it, to see where we want to be in the future. Once we see this, we can work out the steps we must take to get there. Now, and all along the way, self-restraint will be necessary to keep our eyes on the ultimate aim.

“…it belongs to moral virtue to safeguard the good of reason against the passions that rebel against reason.”

Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1485 (published), IIa IIae 141.3

Aquinas did not believe in depriving ourselves of pleasures needlessly, but he did believe that we should show restraint when they no longer serve us and in the name of a better future. Josef Pieper (1965, The Four Cardinal Virtues: Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, Temperance) referred to ‘the infantile disorder of intemperance’; temperance is a virtue of the mature; the ability to reason and restrain oneself from immediately going along with any impulse, for the sake of the greater good.

Order

“It is the concern of temperance to calm all disturbances of the mind and to enforce moderation.”

Cicero, cited in Aquinas, Summa Theologica, 1485 (published), IIa IIae 141.4

Temperance allows order where otherwise there would be chaos. If we gave in to every desire and impulse that we had; if we pursued every fleeting pleasure; our life would be on fire and on a road to nowhere. When there is order, we can see ourselves and our surroundings much more clearly. We can see where we are and where we could be. When there is order, we can aim for an end and move towards it; as oppose to carelessly fulfilling every whim in the pursuit of pleasure. With this, we place order where there is potential for immeasurable chaos.

“Ask God for temperance; that’s the appliance only

Which your disease requires.”William Shakespeare, 1613, Henry VIII, Act I, Scene 1, line 124.

Temperance is a virtue because it allows us to bring moderation, peace and order into our lives. It allows us to stay balanced even when our desires and passions are erratic. Temperance it would seem, is the ability to make choices rather than indulge in impulses. It’s having the foresight to make choices that are better for us, and others, in the long term. It requires sacrifice in the present for the sake of a better tomorrow. Creating harmony and stability, it allows us to move forward towards our ultimate aim. It requires strength and wisdom to employ temperance, but it will not find us lost.

“For therein stands the office of a King,

His Honour, Vertue, Merit and chief Praise,

That for the Publick all this weight he bears.

Yet he who reigns within himself, and rules

Passions, Desires, and Fears, is more a King.”John Milton, 1671, Paradise Regained, Book 2