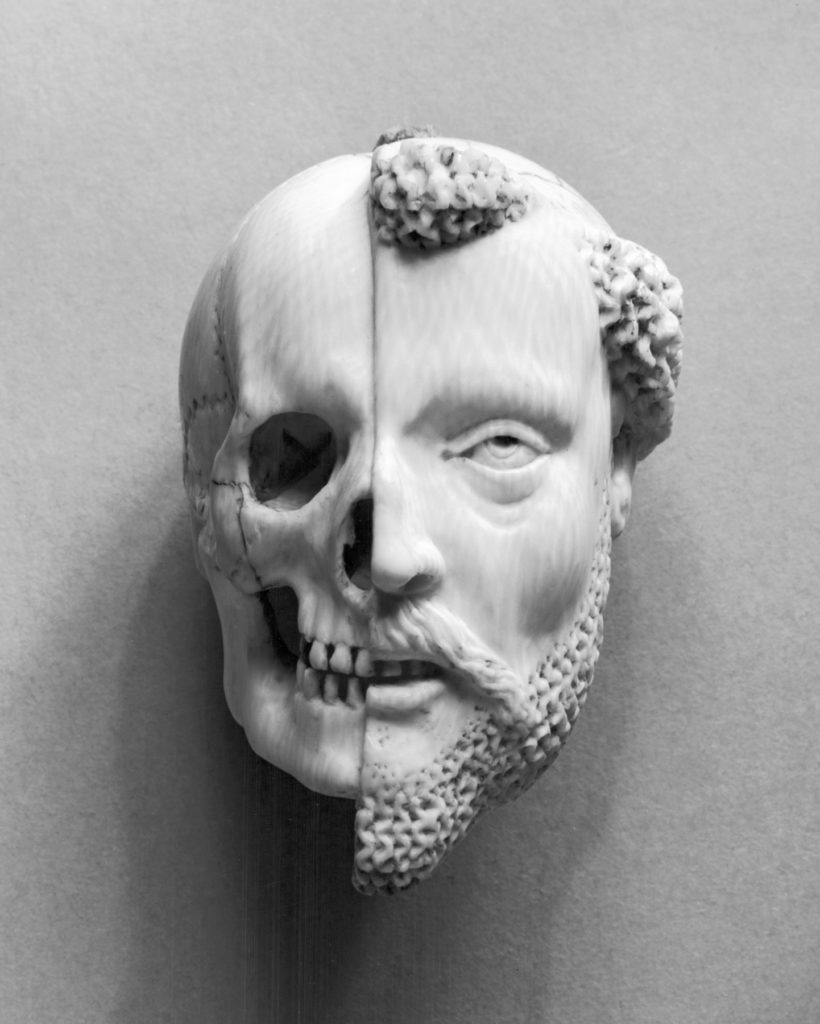

“Never forget that you must die; that death will come sooner than you expect… God has written the letters of death upon your hands. In the inside of your hands you will see the letters M.M. It means ‘Memento Mori’ – remember you must die.”

John Furniss, 1866 (pub), Tracts for Spiritual Reading

From the time of the Ancient Greeks, all the way up to the 20th century, ‘Memento Mori’ was a theory commonly practiced in everyday life.

The idea of Memento Mori was to remember that you will die, and to live closely with this mortality. People throughout history were faced constantly with their own mortality as those around them, very often including children, passed away in their droves. Because of war, poverty, disease and infection, mortality rates were much higher in the past than they are today. This closeness with death is reflected in the music, paintings, sculptures and buildings of the times, which often sported skulls, time pieces, skeletons and other symbols of death and mortality. Thanks to advances in science and technology, we now enjoy far better health and a much greater life expectancy. Death is not constantly knocking on our door, so it has become less a part of our everyday lives.

In ancient philosophy, the Stoics truly lived by ‘Memento Mori’ and spent much of their time musing over death.

They spoke of it, wrote of it and urged others to deeply contemplate it. If they did this in the modern world, we would think them morbid and morose. But these philosophers were anything but. They kept the reality of their own mortality close, so that they wouldn’t waste one moment of being alive. To forget about our own mortality is to become negligent, static and lacklustre. Stoic philosophy believed that having this awareness and acceptance of death was the only way to ensure we would live optimally.

“You are living as if destined to live forever; your own frailty never occurs to you; you don’t notice how much time has already passed, but squander it as though you had a full and over flowing supply-though all the while that very day which you are devoting to somebody or something may be your last”

Seneca, 49 AD, On the Shortness of Life

It is said that in Ancient Rome, a victorious general would return from his battle won, and be put at the centre of a grand procession.

Throughout the celebratory parade, while the crowd sung his praises and glorified his victory, a man, usually a slave, would be behind him repeating the words ‘Respice post te. Hominem te esse memento. Memento mori!’ This meant ‘Look behind you. Remember you are but a man. Remember you will die.’ The victorious general was reminded of his death to instil humility. To remind him that even in this moment when he appears to be on top of the world, he is not free from the grasp of death. Realising our own mortality puts everything else into perspective and keeps things in their correct place of importance.

“Memento mori—remember death! These are important words. If we kept in mind that we will soon inevitably die, our lives would be completely different. If a person knows that he will die in a half hour, he certainly will not bother doing trivial, stupid, or, especially, bad things during this half hour. Perhaps you have half a century before you die—what makes this any different from a half hour?”

Leo Tolstoy, 1911 (pub), Path of Life

To say that our relationship with death has changed over the centuries is an understatement.

We may be glad to leave the Victorian practice of photographing dead relatives in the past, but it would be a mistake to completely disengage with death. To believe that we can shove all thoughts of our mortality to the back of our minds is foolish because it remains an intrinsic part of life. People throughout history knew that there was much to learn in facing our fear of death, growing to accept it and remembering that our time will come to an end. Memento Mori- remember you will die.

“Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot and disappear forever.”

Ernest Becker, 1973, The Denial of Death