“That, when you come down to it, is the only kind of courage that is demanded of us: the courage for the oddest, the most unexpected, the most inexplicable things that we encounter.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, 1904, Letter 8

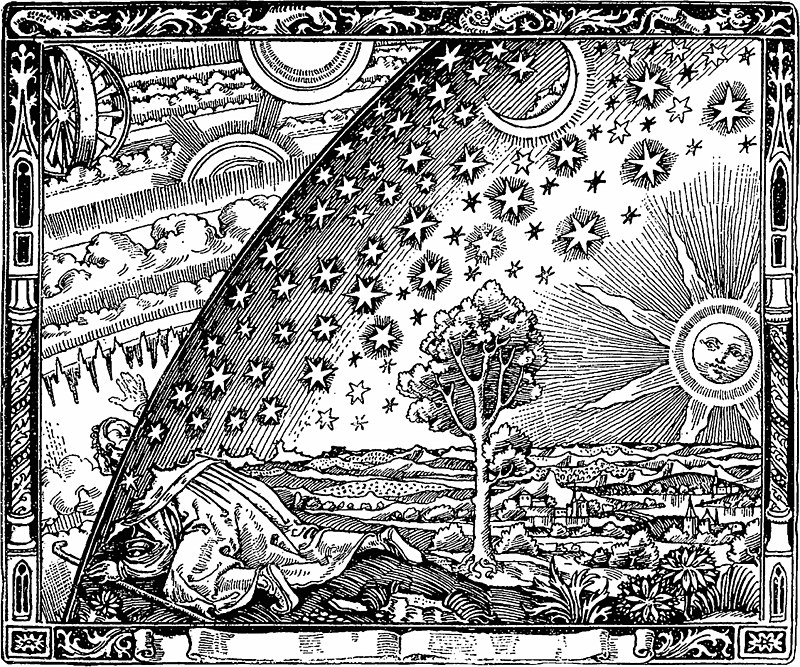

Many years ago, people lived alongside the unknown.

They forged a relationship and co-existed in a world with many elements that were alien to them. Ancient people saw the stars and thought they were holes through which the God’s watched. They saw the constellations and believed they were favoured heroes who had earned a place amongst the stars. Our knowledge and tools developed and we found out a lot about the stars. We know how they come to exist, the elements involved, the physicality of what they are; and as we went on, we found it more difficult to believe them to be heavenly bodies.

Our ability to deconstruct, evaluate and analyse our environment expanded vastly with science and technology. People have always endeavoured to make sense of what they do not know, but they often offered answers which required a huge expansion in thought, asking for belief rather than certainty. The risk in believing our knowledge to be absolute is that we limit our thoughts and cease in our explorations. We should not make the mistake of believing we have it all figured out, the moment we do this, all possibilities evade us.

“That human beings have been cowardly in this regard has done life endless harm; the experiences we describe as ‘apparitions’, the entire so-called ‘spirit world’, death, all those things so closely akin to us have by our daily rejection of them been forced so far out of our lives that the sense with which we might apprehend them have atrophied. To say nothing of God.”

Rilke, 1904, Letter 8

So, in a world where we are given answers rather than coming up with them, with everything explained through the language of science; how can we live with what we don’t know?

There remain mysteries in our world and many to our existence. Rilke, in Letter 8 of ‘Letter’s to a Young Poet’, discusses people’s fear of the inexplicable. We crave to fit all our experiences into manageable and explainable compartments. This is important so that we can make sense of the world around us, for the most part. Rilke acknowledges how difficult it is to surrender to something we do not fully understand or know, comparing it to facing the dizzy heights of a mountaintop, with no surrounding support. He believed that we shy away from the unknown, from possible new experiences because we fear we may not be equal to them.

“Someone transported from his room, almost without warning and interval, onto the top of a high mountain would feel something like it: he would be virtually destroyed by the unparalleled sense of insecurity, by an exposure to something nameless.”

Rilke, 1904, Letter 8

Rilke suggests that we should leave room for the inexplicable because in being open to the unknown, we remain open to possible truths.

He believed that fearing the inexplicable denies us an expansive, true vision of life. It denies us a large part of what makes life so amazing: wonder and possibility. Rilke speaks of human relations being ‘lifted out of the river-bed of endless possibilities and placed on a deserted bank where nothing happens.’ To believe we have discovered all that is and that anything outside of that perimeter is untrue, is a difficult line to live by. If we believe we have all the answers, what is the point? Life becomes lethargic when we refuse to face or recognise the inexplicable: we gain certainty but lose possibility. Although facing the unknown brings us to uncomfortable, insecure places, Rilke believed the alternative is much worse.

“We must accept our existence in as wide a sense as can be; everything, even the unheard of, must be possible within it.”

Rilke, 1904, Letter 8

What’s clear for us to physically see and measure, shows just how amazing our world really is; it is not as if what we know isn’t astounding enough.

What Rilke is urging us to do is to remain open and to continually expose ourselves to the uncomfortable unknown. The inexplicable is possibly as much a part of our reality as the explicable. He is asking that we do not simply dismiss what doesn’t fit into our ideas of what the world is. We should continue to thread on the side of wonder and possibility.

“And if we only organise our life according to the principle which teaches us always to hold to what is difficult, then what now still appears most foreign will become our most intimate and most reliable experience. How can we forget those ancient myths found at the beginnings of all peoples?”

Rilke, 1904, Letter 8